Women still struggle to make it to the top leadership posts in academe

Article and photos from University Affairs

By Rosanna Tamburri | October 5, 2016

Canada’s liberal government was officially sworn in last year on a bright and unseasonably warm November day. Prime Minister Justin Trudeau emerged from Rideau Hall to present his new cabinet to the cheering crowd that had gathered on the grounds of the Governor General’s residence. With 15 men and 15 women, he boasted it was the first gender-balanced ministerial team in the country’s history and “a cabinet that looks like Canada.” When asked why gender parity was important, the prime minister replied with his now famous quip: “Because it’s 2015.”

Despite the positive gesture, gender parity remains a concern in the political arena and indeed in most other spheres. In the corporate world, women hold only a third of senior management positions and account for one-fifth of board seats at major Canadian corporations, according to Catalyst Canada, a research and advocacy organization that promotes the advancement of women in the workplace.

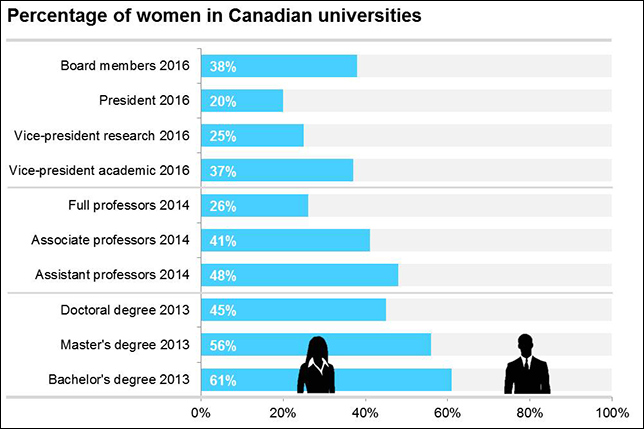

The halls of academia are no exception, although at some levels women’s advancement in higher education has been a success story. Gender parity in student enrolment at Canadian universities was reached in the late 1980s and since then women have come to outnumber men in undergraduate and master’s studies; at the PhD level, women account for nearly half of students. Women also represent half of sessional instructors and more than 42 percent of assistant professors, according to a 2012 report on gender by the Council of Canadian Academies.

Where are the women?

But go higher up the ladder and the story takes a different and all-too-familiar turn. Only 36 percent of associate professors and about 22 percent of full professors are women, the same study notes. Over the 133-year history of the prestigious Royal Society of Canada, only three of its 113 presidents have been women. And the number of women who have led the three major research granting councils can be counted on one hand.

The numbers are equally bleak in the ranks of senior administrators. A study on university leadership by David Turpin, president of the University of Alberta, found that the proportion of women university presidents rose to about 20 percent in the mid-1990s. Since then, despite some minor fluctuations up and down, that level has held more or less steady ever since. As of September 1, 19 of the 97 member universities of Universities Canada are led by women (19.6 percent).

The figures are no better outside Canada’s borders. Data from the 2015-16 Times Higher Education World University Rankings show that just 33 of the top 200 universities in the world (16.5 percent) are headed by women – including Canada’s own McGill University, led by Suzanne Fortier. This is actually an improvement from the 28 universities (14 percent) led by women in the 2014-15 top-200 ranking.

“[Pauline Jewett] was marginalized and seen as an outsider, although by her extensive academic background she should not have been seen that way.”

and Wilfrid Laurier University.

In fairness, women’s contributions to university leadership are more significant than the numbers would suggest. In Canada, women have held the presidency of degree-granting institutions since the early 1900s, although at the time they were relegated to the Catholic-run, women-only schools like Mount Saint Vincent University in Halifax. In a 2004 speech to the Canadian High Commission in London, Lorna Marsden, past president of York University and Wilfrid Laurier University, remarked that the Sisters of Charity who founded and ran MSVU were pioneers in academic administration and curriculum design but weren’t acknowledged as such, overshadowed as they were by their male counterparts and the higher-profile institutions they ran.

It took much longer for women to emerge as leaders outside of MSVU. The first woman appointed president of a co-ed university was the formidable Pauline Jewett, who assumed the helm of Simon Fraser University in 1974. In her biography of the late Dr. Jewett, Pauline Jewett: A Passion for Canada, Judith McKenzie, political science professor at the University of Guelph, paints a vivid portrait of her presidency and ambitious agenda. Among Dr. Jewett’s priorities were to hire Canadian academics at a time when they were often ignored in favour of their U.S. and U.K. counterparts; to expand student access beyond the traditional economic and social elites; and to bring pay levels of female academics in line with those of their male colleagues. But she ran up against fierce resistance and criticism.

Before making the move to SFU, Dr. Jewett had been one of the few women members of Parliament “and was no stranger to patriarchal institutions,” writes Dr. McKenzie. “Yet none of her experiences had prepared her for the intensity of the old boys club mentality that pervaded Simon Fraser.” Frustrated, she cut short her first term and returned to political life.

“She was marginalized and seen by many as an outsider, although by her extensive academic background she should not have been seen that way,” Dr. Marsden told the London audience in her 2004 speech.

More than a decade would pass before another woman would match Dr. Jewett’s accomplishment and move into the corner office: Marsha Hanen at the University of Winnipeg in 1989, followed in quick succession by Geraldine Kenney-Wallace at McMaster University, Elizabeth Parr-Johnston at MSVU, Susan Mann at York University and Dr. Marsden herself, in 1992, at Wilfrid Laurier.

Dr. Marsden credits Janet Wright, president and founder of Janet Wright & Associates, an executive search firm, for these early successes by bringing women candidates to the attention of search committees and governing boards, and ensuring that they were included in presidential search pools. “When Janet was trying to persuade me to let my name stand for president of Wilfrid Laurier University, she had Marsha [Hanen] phone me,” recalls Dr. Marsden. “Janet wasn’t just sourcing names for the search committees, she was mentoring people who could become president. That was a huge breakthrough.”

“as we rise up the ranks there are fewer and fewer women”

The proportion of women leaders continued to climb throughout the 1990s. But then, as Dr. Turpin’s study notes, the numbers stagnated. To this day there are many universities that have never had a woman president. “To me that is shocking,” says Vianne Timmons, president of the University of Regina.

The difficulty with recruiting women to the presidency, in her view, starts further down the pipeline, at the level of provost, vice-president and dean, from which presidents are often chosen. “When I have a VP position open, I get applications primarily from men,” notes Dr. Timmons. “It’s a real concern. Where are the women?”

Academia is by no means an anomaly in this regard. Across sectors and industries, “as we rise up the ranks there are fewer and fewer women,” says Vandana Juneja, senior director of Catalyst Canada. “We see women facing similar challenges and similar barriers” as they strive to move higher up the ladder.

The reasons why are numerous and complex and have little to do with child-rearing and family responsibilities, as is often assumed. Ms. Juneja notes that even among women and men who have made similar life choices – such as to not have children – and who aspire to senior leadership positions, women still lag behind. “There are other factors at play,” she says. These include systemic barriers such as a dearth of senior role models that can make it difficult for women to envisage themselves in leadership roles; a lack of access to informal networks and senior level mentors and sponsors; and deeply ingrained biases in hiring and promotion practices.

Aggravating the situation, in Dr. Timmons’ view, is the high degree of public scrutiny that women in these positions are now under. She says she’s astounded by the number of negative comments made about her on social media that refer specifically to her gender. “I don’t care so much when [the comments] are about my clothes or my hair or my voice even. But when it’s about my parenting, or being a mother, those I find a little more challenging,” she says. “Sometimes it cuts to the quick.”

“They think they can bully you a little bit more, they can push you around a bit”

Still, she reads the messages and shares them when making presentations to senior administrators and at leadership forums she hosts for women in the community. “Women leaders need to be prepared for what they can face,” she says. “I don’t want to whitewash it.” On the other hand, she also emphasizes the many positive aspects of her job. “There’s not a day I don’t feel that I’m making a difference. That’s critical.”

Not only are women less likely to hold the top job at a university, but once having attained it, they are also more likely to have a mandate cut short. According to Julie Cafley, vice-president of the Ottawa-based Public Policy Forum, the last six of eight presidents with unfinished mandates have been women. (Likewise, U of A’s Dr. Turpin told the Globe and Mail that he and his research colleagues recently updated their analysis of university presidents and also found that this is happening with greater frequency to women than to men.) Several former presidents that Dr. Cafley interviewed for her PhD research, both male and female, spoke of “a dominant male culture” within Canadian universities, especially at the board level and in senior leadership teams – not that different from what Dr. Jewett encountered more than 40 years ago.

“It was a very, very male world,” said one former male president to Dr. Cafley. “It was a very distasteful experience for me because it was my first real encounter with [an] old boys club and all the negative connotations that that meant.”

Another participant in Dr. Cafley’s research, a woman, confided: “People don’t take you seriously … They don’t think you know about numbers and money … They think they can bully you a little bit more, they can push you around a bit.”

Most recently, one woman’s rise to university president ended before it even began. Wendy Cukier, formerly vice-president, research and innovation, at Ryerson University and founder of its Diversity Institute, was scheduled to take over as Brock University’s first female president on Sept. 1. However, just days before it was to take effect, the chair of Brock’s board of trustees, John Suk, announced that the appointment was cancelled in a “mutual decision.” Few other details were given. Linda Rose-Krasnor, a psychology professor and president of the Brock University Faculty Association, said the news “left many of us in a state of shock [and] confusion.”

“If we want to see women moving into these positions, we need to socialize search firms and boards to look at different pathways in for women.”

In an effort to overcome some of the barriers women face, Universities Canada officially launched last year a network of women presidents. Among other things, the initiative aims to develop a supportive network to mentor newly appointed women presidents as well as those who aspire to the presidency; to seek out speaking engagements and other opportunities to raise the profile of its members; and to ensure that they are nominated for top honours such as the Order of Canada and the Killam Prize.

“My hope for the network is that it will be an environment that can help to promote the value of women in executive-head positions, that can provide sponsorship opportunities for women … but also can do some advocacy in the broader context,” says Sara Diamond, president of OCAD University.

One issue the network hopes to tackle is finding ways to ensure equity and diversity on university governing boards and to foster boards that will support women presidents. “If we want to see women moving into these positions, we really need to socialize search firms and boards to look at different pathways in for women,” Dr. Diamond says, and to ensure that women make their way up the appropriate ladders within academia so that they acquire the skills that are attractive to search firms and boards. “The kind of skill set that is increasingly required for these roles is pretty wide and there isn’t that much training within that path up the ranks,” she says.

A panel of women presidents spoke about the importance of diversity at this year’s annual conference of the Canadian University Boards Association held in Halifax in April. The advancement of women’s leadership was also a major topic of discussion at the Universities Canada membership meeting in Toronto that same month. Bill Thomas, chief executive officer of KPMG Canada, addressed the latter meeting and spoke about the strides his own organization has made in appointing women to leadership positions.

An unconscious bias

Mr. Thomas said the biggest barrier to women’s advancement is unconscious bias. He challenged all presidents to think about the leadership teams at their own institutions and what changes could be made to ensure that women have an opportunity to participate fully in its leadership. Universities Canada President Paul Davidson says his organization is offering unconscious bias training for university presidents similar to the training that KPMG used. “This is an urgent challenge. It’s an ongoing challenge,” Mr. Davidson says.

In another effort to promote gender diversity, Universities Canada recently changed its bylaws regarding regional representation on its executive board. The goal is to have women eventually make up half of the board, says Mr. Davidson, and have it reflect the true diversity of the country.

Canada’s French-speaking universities are taking part in a broader initiative. The Agence universitaire de la Francophonie, a group that represents the world’s francophone universities, launched a network of senior women administrators two years ago. The network plans to run a mentorship program to encourage women to seek out leadership positions, including those of dean, vice-president and president. It soon hopes to launch a centralized agency that will track the number of women in these roles at the more than 800 French-speaking universities around the world and conduct research on what hurdles stand in the way of their advancement.

The work will be especially significant for universities in regions such as francophone Africa, where women academics lag far behind their male counterparts, says Marie-Linda Lord, former vice-president of students and international affairs at Université de Moncton. But its impact could extend well beyond French-speaking countries since francophone universities are also found in English-speaking regions, says Dr. Lord, who sits on the women’s network as vice-chair of the Americas region. “Even in Canada, it’s a male world, with male frameworks of thinking and male ways of doing things,” she says. The network will be open to men as well as women, adds Dr. Lord. “We have to engage in a dialogue. We have to avoid marginalizing ourselves.”

“There are some deeply embedded challenges that women in academia face that have to be addressed”

and innovation, Ryerson University.

Governments can also play a role by continuing to ask questions about why “the vast majority” of government-sponsored research funds in the country goes to male researchers, says Ryerson’s Dr. Cukier (she was interviewed prior to the announcement that she was no longer moving to Brock). Dr. Cukier notes that research conducted by Ryerson’s Diversity Institute shows that women account for only 29 percent of Canada Research Chairs, 7.7 percent of Canada Excellence Research Chairs (this has since dropped to 3.7 percent), and 14 percent of Ontario Research Fund – Research Excellence recipients.

As well, institutions should strive to implement bias-free recruiting and promotion processes, and to provide access to mentoring, coaching and leadership-development opportunities that are now commonplace in the corporate sector, says Dr. Cukier. “There are some deeply embedded challenges that women in academia face that have to be addressed,” she says.

The benefits of achieving a diverse and inclusive workplace will ultimately be reaped by institutions as well as the individuals involved, says Catalyst’s Ms. Juneja. These include improved financial performance, better decision-making, greater creativity and innovation, and enhanced attraction and retention of employees. “Universities, like other organizations, need to engage both men and women in leadership positions in order to really leverage the full potential of their talent,” she says. “This isn’t a gender issue. It’s a talent issue.”